Why I Stopped Reading Arts and Letters Daily

by Nemo

Do academics have a responsibility to reach beyond the narrow confines of their disciplines? Does scholarship, specialized by its very nature, translate well into broader public discourse? What exactly is the difference between an “academic” and an “intellectual”? How do they overlap and where exactly do they differ?

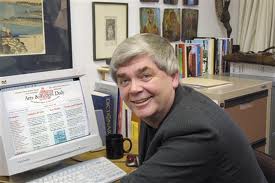

Philosopher Denis Dutton, who died last week at the age of 66, presents a telling example of a scholar who attempted to bridge the gap between academic rigor and public accessibility. In 1999, Dutton founded what would become the popular website Arts and Letters Daily. A high-brow (and infinitely more sophisticated) version of the Drudge Report, the site provided links to what Dutton and his editorial partner, economist Tran Huu Dung, considered the web’s best articles, op-eds, and book reviews. Often eclectic, the links could treat everything from Ancient Roman historiography, developments in economic theory, to the relationship between ideology and bathroom etiquette. At the height of its influence in the early 2000s, it was probably one of the most widely read blogs among American academics. As a young college student aspiring to greater intellectual heights, I made it my homepage.

The site was popular among scholars in spite of the fact that it routinely linked to articles mocking academic pretensions (although it’s equally plausible that this helped explain its success). Dutton despised the turgid prose that he believed dominated academic writing and frequently linked to articles that lamented its dominance. As editor of the journal Philosophy and Literature, he even launched a “Bad Writing Contest” in which correspondents submitted the most egregious examples of such prose that they had found in an academic text. Since Dutton also hated critical theory’s influence on scholarship—which he considered little more than an academic fad—it was not surprising that theorists such as Homi K. Bhabha, Frederick Jameson, and Judith Butler were all awarded the bad writing prize (the difficulty of their prose, however, certainly didn’t help). Dutton rejected many of his academic colleagues focus on discourse, power, and difference, and instead used his perch at Arts and Letters to champion the human universalism implied by much work in evolutionary psychology—an entire field treated with skepticism by most scholars in the social science and the humanities. (His recent book, The Art Instinct: Beauty, Pleasure, and Evolution, applies insights from evolutionary psychology to aesthetic theory.)

The apparent contrarianism conveyed in the articles on Arts and Letters helped make it a formative influence on my own intellectual development. I started reading the site at the age of 18 and it introduced me to the world of public intellectuals. I devoured essays by the likes of Christopher Hitchens, Andrew Sullivan, and Martha Nussbaum. Arts and Letters convinced me that serious public discourse required style, sophistication, and skepticism. I began reading the site as a fairly dogmatic liberal, but its frequent links to conservative intellectuals and unclassifiable political heretics helped me to constantly reassess my own positions. Perhaps most importantly, Arts and Letters introduced me to an expansive and evolving intellectual community. In fact, my exposure to the site probably played an important role in my decision to pursue American intellectual history as a graduate student.

Since it has exerted such a strong affect on my intellectual development, it’s been sad for me to gradually give up on reading the site, and it seems as though I’m not the only one. Some of this has to do with the proliferation of new sites competing for intellectually-engaged readers, but I believe there are broader reasons for its relative decline. For me, and I’m sure for many others, Arts and Letters’ linking choices during the first few years of the Iraq War damaged its credibility. While occasionally highlighting pieces by the war’s opponents, during this period, the site mostly provided a steady barrage of links to the war’s intellectual cheerleaders—whether they were neo-conservatives such as David Frum, “Burkean” conservatives such as Andrew Sullivan, left-wing apostates such as Christopher Hitchens, or “liberal hawks” such as Peter Beinart. These writers believed that Iraq contained Weapons of Mass Destruction, that America could create the foundation for a democratic Middle-East with relatively little bloodshed, and routinely questioned the motives of the war’s opponents. The vitriol such thinkers expressed for the war’s critics is difficult to remember in our current era when a majority of Americans (and an even broader portion of intellectuals) consider the war a huge failure, which did little but empower Iran and cost hundreds and thousands of lives in the process.

At the time, I did not see these articles as the embarrassment they would later become to some of their authors, but I did feel that their enthusiasm for war and the certainty with which they defended their cause, troubling. As the years went on, and the evidence of the war’s failures became apparent, I came to believe that Arts and Letters had let its readers down. The site had constantly lauded the values of intellectual rigor and skepticism, but did much to promote the views of the war’s loudest and most misinformed supporters.

Dutton’s development of an online forum, prominently advertised on Arts and Letters, devoted to debating the reality of climate change represented the next blow to the site’s credibility. The fact that Dutton, who considered himself a vigorous proponent of the scientific method, would give equal time to the scientifically marginalized (and industry beloved) deniers of global warming, as if a serious “debate” was actually taking place marked a major turning point in my trust for the site. When I first saw the advertisement for Dutton’s climate change project on Arts and Letters, my heart sank. I felt less anger than disappointment for a website that had one exerted such an influence on my intellectual development.

Finally, I stopped reading Arts and Letters a few years ago because of my ongoing “professionalization” into the world of academe. Let me illustrate with an example: as a freshman, I once sent a link to aldaily to an art history professor that I respected: I thought she would be impressed. Instead, she told me that many of the articles were right-wing polemics and that all lacked the rigor of peer-review. At the time (and to an extent, to this day), I felt taken aback by her pronouncements: the site was not conservative, I thought, it just frequently attacked liberal pieties. Plus, I didn’t think everything needed to be peer-reviewed—the site was up to date, relevant, and lacked the dryness that I had come to associate with much academic writing. This was how public debate moved forward.

Over the years, however, I came to understand my professor’s position. Once I started to actually read writers such as Foucault, Derrida, and Butler, I realized that many of the denunciations launched against them—frequently promoted on Arts and Letters Daily—were unfair, to say the least. I still refuse to genuflect toward any intellectual authority, but such theorists have triggered debate because their ideas are often profound, complex, and troubling—they need to be treated with intellectual seriousness. Of course, all of these figures are worthy of critique, but this is very difficult to do well in an op-ed format often better suited for polemical takedowns.

This brings me back to my original question about academics navigating the world of public discussion. Many scholars already cringe when they are forced to trim their research down to fit a 10-page conference papers; an op-ed generally cuts that material down to 2 pages. Translating specialized academic training into the often intimate, humorous, and generalist medium of blogging represents a serious challenge, but in the past few years, many have risen to meet it. These sites generally succeed because they refuse to dumb down expert knowledge even as they make it more accessible, avoid fruitless polemics, treat claims to infallibility with skepticism, and make valuable contributions to public debate. Even though I stopped reading it, these are all points that, at its best, Arts and Letters Daily continues to encourage.

Great article. A&LD has been an ebb and flow website for me over the past 10 years. I have renounced it at one point only to return to it like a scorned lover.

Which reminds me: I haven’t checked the site in over a year.

*googles Arts & Letters Daily*

Aaron

January 4, 2011 at 20:41

Yeah, for a while in college I had Arts and Letters as my homepage. I took it off at some point and replaced it with BBC. To me, in a way that I couldn’t really articulate at the time, I remember just feeling annoyed at the tone. Those were serious scary times, with the Iraq war, freedom fries, and little American flags everywhere. I just felt like the whole atmosphere of it was one of self-satisfied superiority towards the anti-war crowd, as if we were barely worth taking seriously. There are times when the academic love of comfortable and self-congratulating openness to all sides of a debate seems out of place; when you just want to grab someone by the shoulders and figure out what side they are on.

Wiz

January 4, 2011 at 22:11

Thanks for the comments Aaron. Like you, I went back to the Arts and Letters site when writing this piece. I saw teasers on the poor state of prose writing, the evils of Soviet totalitarianism, and an attack on Tariq Ramadan: doesn’t seem like much has changed in the past few years.

Wiz: Totally agree. One of the things that bothered me about Arts and Letters over the years was the way its veneer of sophisticated even-handedness actually masked a “centrist” self-congratulation that had little tolerance for radicalism of any kind. If the site was actually ideologically balanced, I might still read it.

nemo

January 4, 2011 at 23:14

Nice post Nemo. I never regularly read Arts and Letters even in its heyday because, well, while you were a dogmatic liberal I was a dogmatic leftist and suspected its right-wing pretensions immediately. I might be more likely to read it now, not out of sympathy, of course, but because I’ve expanded my ideological reading.

Your penultimate paragraph mostly sums up the conservative attack on left-wing academics in the culture wars. They scored easy cheap shots but rarely if ever took the ideas of the scorned tenured radicals seriously.

Andrew Hartman

January 4, 2011 at 23:26

The problem, gents, is that you have no will to fight for all you have been given. It makes you uncomfortable to know that people have been murdered in mass quantities in order that you can sit at your computer and pretend that pacifism is morally superior. You can’t understand that if the oil stops flowing and economies start weakening, millions die of starvation in the poorest countries, medicines don’t get invented, every stops coming to the doorstep of ingrates.

Kev fors

February 16, 2011 at 08:50

For the record there are some ladies on this blog. I realize this can be hard to remember for those who tap at their computers with the weight of world survival on their shoulders.

luce

February 16, 2011 at 15:25

Hi, I was hoping that someone could point me in the direction of similar sites to Arts and Letters daily? I enjoy the site’s material ( with a healthy dose of skepticism of course ) and am seeking to increase my intellectual capacities – for lack of a better phrase.

Thank you.

Walt

July 19, 2011 at 23:48

three quarks daily

Mysti

September 25, 2011 at 10:22

In other words you can’t stand to read anything that mihght upset your prejudices. Censor it! How contemptible you sound!

Kevin Dunn

August 17, 2011 at 23:50

Nice piece. Just found a good article by Dorfman, the Chilean leftist on Arts and Letters which made me think it might be worth reading again. Then I found your piece and am now echoing Walt’s question: where is the site that Arts and Letters fails to do?

Farrell

Farrell

September 19, 2011 at 06:11

I mean, “where is the site that does what “Arts and Letters Daily” fails to do?

Farrell

September 19, 2011 at 06:12

A little late to this conversation, but I must chime in; you basically quit reading “Arts and Letters Daily” when it failed to pander to your liberal, leftist thinking. How intellectual of you…contemptible, indeed. I quit reading the same day I was referred, after reading an extremely excruciating and sophomoric article on Why Jews and Gentiles parted ways. I love it when people write long-winded articles on social theology when they are clearly out of their depth. Perhaps that bad writing award should just be passed out in-house.

Beth

December 17, 2011 at 11:24

I wonder what he would think about the dearly departed “Lingua Franca” magazine ? See: online archive

Phil Taylor

January 10, 2012 at 15:18

Arts and Letters Daily points the chattering classes towards those matters thought worthy of chattering about. It is also helpful in suggesting HOW these matters ought to be chattered about. In short, the framing comes gratis. That framing is then adopted by public radio/tv “current affairs” producers as well as by editorial writers and columnists. Thus doth the “required” consensus make its way from the Palazzo to the Piazza. A good rule of thumb when reading compilations such as ALD is to “interrogate the absences,” just as one might use BBC World Service to interrogate the absences at CNN–not the most demanding of tasks–and then to use Al Jazeera to ask questions about BBC’s more deft footwork. And then, of course, to examine Al Jazeera. As for alternatives to ALD, I find Counterpunch more lively and well-informed; whether you agree with it is up to you.

Patrick MacFadden

January 16, 2012 at 13:29

Try http://www.abc.net.au Australia’s national broadcaster for a different slant BBC is great too but an Australian flavour can be interesting in a different way

Georgia Cummings

July 4, 2014 at 18:41

I dunno, man. I don’t see the “difficulty” of Judith Butler’s writing being a major source of trouble. But, then, bad writing isn’t really her problem, either. “Bad writing” was really code for *nonsense.* And she’s guilty on that charge.

I, too, always thought ALD was more iconoclastic than cranky conservative…but I missed the Iraq war stuff and the climate stuff. That’s embarrassing alright. Still, I’d say, a handy source of fun/interesting links.

Winston Smith

January 18, 2012 at 13:42

Isn’t it enough that A&Ld provides food for thought? Why politicize it and bombard it with time-filling polemics?

robert meister

January 24, 2012 at 03:04

I read A& L regularly. A wide spectrum of opinion is represented, which is probably why dogmatic liberals

dislike it. They only like to see their own opinions represented.

If there are people who deny climate change I would like to know their reasons so I can evaluate them for myself, rather than censoring them, as the author of this article would do.

JM Gowans

February 11, 2012 at 05:06

Your grammar is atrocious, Nemo.

Joel

February 11, 2012 at 20:37

I trust the marketplace of ideas over the cozy world of peer review.

Jim Finnegan

February 29, 2012 at 20:17

If you actually apply the standards that the author claims, then you wouldn’t read this site either.

So be it.

j.a.m.

March 11, 2012 at 20:58

Walt, try Omnivore Book Forum.

JT

July 26, 2012 at 11:48

So as you became more deeply inculcated into insular academic world, opposing viewpoints became more odious to you. A little too much deference to a left wing art professor doesn’t like an article you like. But again, this is academia, it’s all petty, I get it.

Just last month there was a brilliant review of a biography on Derrida, front and center. Sure it was critical, but then again, Derrida deserved it, and the article took his ideas seriously.

This article has some shoddy logic and some tortuous rationalizations and really proves the poverty of academia, not A&LD.

Gabriel Rom

December 12, 2012 at 00:19

So A&LD isn’t perfect? Okay. But why would you even bother making the point? Attention-seeking? Nemo, I suggest you take yourself less seriously.

LenO

July 22, 2014 at 14:46

Peer review has become the problem not the solution. It prevents advancement.

David

December 3, 2013 at 17:16

The pretentious academics so successfully skewered by the bad writing prize would probably have enjoyed reading A&LD early in their careers, before they became addicted to verbal onanism.

Tim

September 24, 2014 at 15:02

Agree with concern about the tone. Almost wholly cynical and bleak. Must it be so? I,too, thought it the mother lode of literary delight–at first. But as a person inclined to dark pessimism, it came to seem relentless, and dreary.

Tim T

January 23, 2015 at 17:36

‘Right wing polemics without peer review…’ Can anyone imagine an essay by Hannah Arendt being peer reviewed? Your prof needs to make up her own mind about opinion pieces, and decide for herself whether the case has been made by the author. Peer review makes sense in the natural sciences where there may be very few specialists in the world who can assess the methods, and the way the data were arrived at. In all other branches of knowledge, we can make up our own minds. I lean very far to the left, but I am happy to read pungent intelligent right wingers; in fact I MUST read them because otherwise I don’t know how to answer their charges. What’s your prof afraid of? That she might actually be seduced by the opposition’s arguments?

J Vernon

May 5, 2015 at 11:35